-

- \ No newline at end of file

+

diff --git a/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md b/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

index 008f4f7..22e7ea0 100644

--- a/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

+++ b/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

@@ -35,36 +35,34 @@ In a recent New York Times [article](http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/30/science/t

-Because the real story (or non-story) is way too boring to sell newspapers, the author resorted to a sensationalist narrative that went something like this: "Evil and/or stupid frequentists were ready to let a fisherman die; the persecuted Bayesian heroes saved him." This piece adds to the growing number of writings blaming frequentist statistics for the so-called reproducibility crisis in science. If there is something Roger, [Jeff](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/11/26/statistical-zealots/) and [I](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/08/01/the-roc-curves-of-science/) agree on is that this debate is [not constructive](http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/bayesian-vs-frequentist-is-there-any.html). As [Rob Kass](http://arxiv.org/pdf/1106.2895v2.pdf) suggests it's time to move on to pragmatism. Here I follow up Jeff's recent post by sharing related thoughts brought about by two decades of practicing applied statistics and hope it helps put this unhelpful debate to rest.

+Because the real story (or non-story) is way too boring to sell newspapers, the author resorted to a sensationalist narrative that went something like this: "Evil and/or stupid frequentists were ready to let a fisherman die; the persecuted Bayesian heroes saved him." This piece adds to the growing number of writings blaming frequentist statistics for the so-called reproducibility crisis in science. If there is something Roger, [Jeff](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/11/26/statistical-zealots/) and [I](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/08/01/the-roc-curves-of-science/) agree on is that this debate is [not constructive](http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/bayesian-vs-frequentist-is-there-any.html). As [Rob Kass](http://arxiv.org/pdf/1106.2895v2.pdf) suggests it's time to move on to pragmatism. Here I follow up Jeff's [recent post](http://simplystatistics.org/2014/09/30/you-think-p-values-are-bad-i-say-show-me-the-data/) by sharing related thoughts brought about by two decades of practicing applied statistics and hope it helps put this unhelpful debate to rest.

+

-

\ No newline at end of file

+

diff --git a/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md b/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

index 008f4f7..22e7ea0 100644

--- a/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

+++ b/_posts/2014-10-13-as-an-applied-statistician-i-find-the-frequentists-versus-bayesians-debate-completely-inconsequential.md

@@ -35,36 +35,34 @@ In a recent New York Times [article](http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/30/science/t

-Because the real story (or non-story) is way too boring to sell newspapers, the author resorted to a sensationalist narrative that went something like this: "Evil and/or stupid frequentists were ready to let a fisherman die; the persecuted Bayesian heroes saved him." This piece adds to the growing number of writings blaming frequentist statistics for the so-called reproducibility crisis in science. If there is something Roger, [Jeff](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/11/26/statistical-zealots/) and [I](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/08/01/the-roc-curves-of-science/) agree on is that this debate is [not constructive](http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/bayesian-vs-frequentist-is-there-any.html). As [Rob Kass](http://arxiv.org/pdf/1106.2895v2.pdf) suggests it's time to move on to pragmatism. Here I follow up Jeff's recent post by sharing related thoughts brought about by two decades of practicing applied statistics and hope it helps put this unhelpful debate to rest.

+Because the real story (or non-story) is way too boring to sell newspapers, the author resorted to a sensationalist narrative that went something like this: "Evil and/or stupid frequentists were ready to let a fisherman die; the persecuted Bayesian heroes saved him." This piece adds to the growing number of writings blaming frequentist statistics for the so-called reproducibility crisis in science. If there is something Roger, [Jeff](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/11/26/statistical-zealots/) and [I](http://simplystatistics.org/2013/08/01/the-roc-curves-of-science/) agree on is that this debate is [not constructive](http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/bayesian-vs-frequentist-is-there-any.html). As [Rob Kass](http://arxiv.org/pdf/1106.2895v2.pdf) suggests it's time to move on to pragmatism. Here I follow up Jeff's [recent post](http://simplystatistics.org/2014/09/30/you-think-p-values-are-bad-i-say-show-me-the-data/) by sharing related thoughts brought about by two decades of practicing applied statistics and hope it helps put this unhelpful debate to rest.

+

-Applied statisticians help answer questions with data. How should I design a roulette so my casino makes $? Does this fertilizer increase crop yield? Does streptomycin cure pulmonary tuberculosis? Does smoking cause cancer? What movie would would this user enjoy? Which baseball player should the Red Sox give a contract to? Should this patient receive chemotherapy? Our involvement typically means analyzing data and designing experiments. To do this we use a variety of techniques that have been successfully applied in the past and that we have mathematically shown to have desirable properties. Some of these tools are frequentist, some of them are Bayesian, some could be argued to be both, and some don't even use probability. The Casino will do just fine with frequentist statistics, while the baseball team might want to apply a Bayesian approach to avoid overpaying for players that have simply been lucky. -

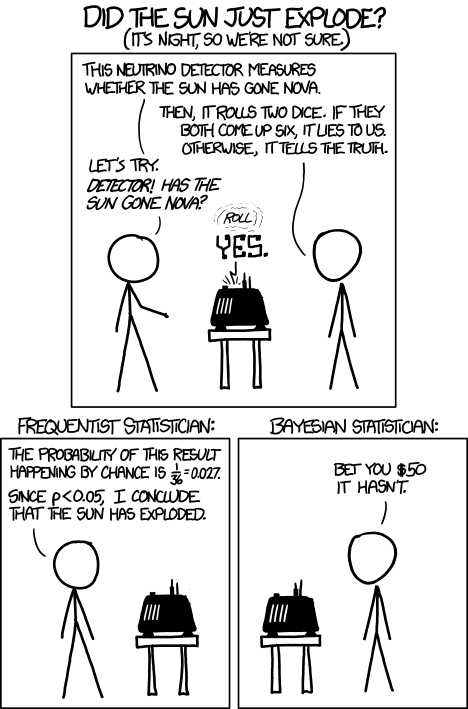

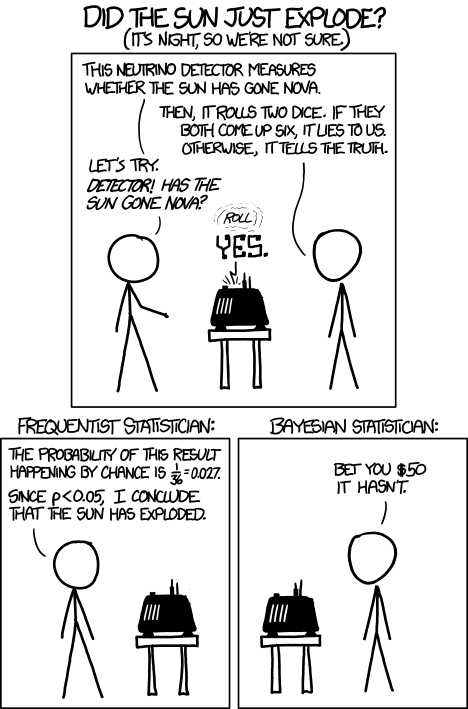

-- It is also important to remember that good applied statisticians also *think*. They don't apply techniques blindly or religiously. If applied statisticians, regardless of their philosophical bent, are asked if the sun just exploded, they would not design an experiment as the one depicted in this popular XKCD cartoon. -

-

+

+ It is also important to remember that good applied statisticians also **think**. They don't apply techniques blindly or religiously. If applied statisticians, regardless of their philosophical bent, are asked if the sun just exploded, they would not design an experiment as the one depicted in this popular XKCD cartoon.

+

+

+

-

-

+ + Only someone that does not know how to think like a statistician would act like the frequentists in the cartoon. Unfortunately we do have such people analyzing data. But their choice of technique is not the problem, it's their lack of critical thinking. However, even the most frequentist-appearing applied statistician understands Bayes rule and will adapt the Bayesian approach when appropriate. In the above XCKD example, any respectful applied statistician would not even bother examining the data (the dice roll), because they would assign a probability of 0 to the sun exploding (the empirical prior based on the fact that they are alive). However, superficial propositions arguing for wider adoption of Bayesian methods fail to realize that using these techniques in an actual data analysis project is very different from simply thinking like a Bayesian. To do this we have to represent our intuition or prior knowledge (or whatever you want to call it) with mathematical formulae. When theoretical Bayesians pick these priors, they mainly have mathematical/computational considerations in mind. In practice we can't afford this luxury: a bad prior will render the analysis useless regardless of its convenient mathematically properties. -

-- Despite these challenges, applied statisticians regularly use Bayesian techniques successfully. In one of the fields I work in, Genomics, empirical Bayes techniques are widely used. In this popular application of empirical Bayes we use data from all genes to improve the precision of estimates obtained for specific genes. However, the most widely used output of the software implementation is not a posterior probability. Instead, an empirical Bayes technique is used to improve the estimate of the standard error used in a good ol' fashioned t-test. This idea has changed the way thousands of Biologists search for differential expressed genes and is, in my opinion, one of the most important contributions of Statistics to Genomics. Is this approach frequentist? Bayesian? To this applied statistician it doesn't really matter. -

-

- For those arguing that simply switching to a Bayesian philosophy will improve the current state of affairs, let's consider the smoking and cancer example. Today there is wide agreement that smoking causes lung cancer. Without a clear deductive biochemical/physiological argument and without

the possibility of a randomized trial, this connection was established with a series of observational studies. Most, if not all, of the associated data analyses were based on frequentist techniques. None of the reported confidence intervals on their own established the consensus. Instead, as usually happens in science, a long series of studies supporting this conclusion were needed. How exactly would this have been different with a strictly Bayesian approach? Would a single paper been enough? Would using priors helped given the "expert knowledge" at the time (see below)?

-

+ Despite these challenges, applied statisticians regularly use Bayesian techniques successfully. In one of the fields I work in, Genomics, empirical Bayes techniques are widely used. In [this](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16646809) popular application of empirical Bayes we use data from all genes to improve the precision of estimates obtained for specific genes. However, the most widely used output of the software implementation is not a posterior probability. Instead, an empirical Bayes technique is used to improve the estimate of the standard error used in a good ol' fashioned t-test. This idea has changed the way thousands of Biologists search for differential expressed genes and is, in my opinion, one of the most important contributions of Statistics to Genomics. Is this approach frequentist? Bayesian? To this applied statistician it doesn't really matter.

+

+

+

+ For those arguing that simply switching to a Bayesian philosophy will improve the current state of affairs, let's consider the smoking and cancer example. Today there is wide agreement that smoking causes lung cancer. Without a clear deductive biochemical/physiological argument and without the possibility of a randomized trial, this connection was established with a series of observational studies. Most, if not all, of the associated data analyses were based on frequentist techniques. None of the reported confidence intervals on their own established the consensus. Instead, as usually happens in science, a long series of studies supporting this conclusion were needed. How exactly would this have been different with a strictly Bayesian approach? Would a single paper been enough? Would using priors helped given the "expert knowledge" at the time (see below)?

+

+

+

-

-

+ And how would the Bayesian analysis performed by tabacco companies shape the debate? Ultimately, I think applied statisticians would have made an equally convincing case against smoking with Bayesian posteriors as opposed to frequentist confidence intervals. Going forward I hope applied statisticians continue to be free to use whatever techniques they see fit and that critical thinking about data continues to be what distinguishes us. Imposing Bayesian or frequentists philosophy on us would be a disaster. -